'Sadovyi' and the Memory War

ALA scandal revisited. University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. More clues about convergence of CIA and Bandera cult. Early days of the memory war in Ukraine.

Note to subscribers: Substack says this post is “too long for email.”

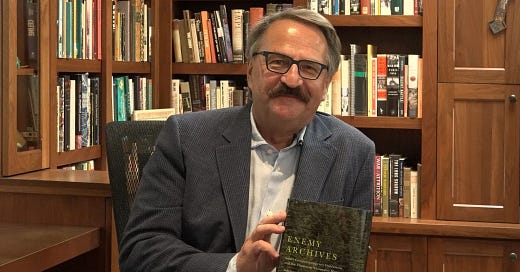

This year the “Bandera Lobby” suffered an emotional rollercoaster when the American Library Association (ALA) only temporarily recognized Enemy Archives: Soviet Counterinsurgency Operations and the Ukrainian Nationalist Movement – Selections from the Secret Police Archives as “one of the Best Historical Materials published in 2022 and 2023.” The award was rescinded after Lev Golinkin wrote an article for The Nation, which asked why the ALA is “Whitewashing the History of Ukrainian Nazis.”

Enemy Archives was compiled by a pair of prominent Banderite memory warriors. Lubomyr Luciuk, whose ex-wife leads the Ukrainian Canadian Congress, might not be a sworn member of OUN-B, or the “Banderite” faction of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, which still exists. Luciuk’s co-editor, on the other hand, doesn’t have as much plausible deniability. Volodymyr Viatrovych served as the “memory czar” of Ukraine (2014-19) only after he led the “Center for Research of the Liberation Movement” (TsDVR, Tsentr Doslidzhenʹ Volʹovoho Rukhu), an important OUN-B front group that has embedded its leaders in the state-run Institute of National Memory and the Ukrainian successor of the KGB over the past 10-20 years.

Something I did not mention in my post about “Bojczukgate”: twenty years ago, the OUN-B assembled an international commission to investigate that scandal at the request of “Sadovyi,” the acting “Land Leader of America” in 2004-2005. “Sadovyi” was Dmytro Shtohryn, the longtime chairman of the Ukrainian Library Association of America (1967-85) and the grandfather of Ukrainian studies at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. He co-founded the TsDVR and reportedly chaired the ALA’s Slavic and East European Section for years.

Over the Fourth of July weekend in 2001, the “Conference of Ukrainian Statehood Organizations” (coalition of OUN-B “facade structures”) in the United States held the 51st annual “Meeting of Ukrainians of America” at a Banderite summer camp in Ellenville, New York. During the Cold War, this was a point of pilgrimage for OUN-B members as the home of the oldest Banderite monument in the world, which remains a quasi-religious site for some. The 2001 “Meeting of Ukrainians” was dedicated to the 10th anniversary of Ukrainian independence, and the 60th anniversary of the “Act of Restoration of the Ukrainian State” on June 30, 1941, when the OUN-B tried to establish a pro-Nazi government in German-occupied western Ukraine.

The Banderites held a panel discussion about these anniversaries, in the presence of youngsters from an ongoing “educational” camp named after Dmytro Dontsov (1883-1973), the grandfather of genocidal Ukrainian fascism. Walter Zaryckyj, executive director of the Center for US-Ukrainian Relations (CUSUR, est. 2000), which was the latest OUN-B front group in the United States, moderated the discussion. The main panelist was Andriy Haidamakha, the new OUN-B leader from Belgium, who spent the past decade running the Kyiv bureau of the US-funded “Radio Svoboda.” At least three speakers came from (western) Ukraine:

Oleksandr Sych, the future ideologist of the far-right “Svoboda” party, which was established in 2004 after a nationalist rebranding of the neo-Nazi “Social-National Party.” In 2003, Sych spoke at a CUSUR conference in Washington. He returned in 2014 as a Vice Prime Minister of Ukraine.

Ihor Symchych, secretary general of the OUN-B’s international Ukrainian Youth Association. His father, Myroslav Symchych, a veteran of the OUN-B’s Ukrainian Insurgent Army and reportedly a war criminal, lived to be 100 hundred years old. At 99, Zelensky decreed him a “Hero of Ukraine” (2022).

Bohdan Lavonyk, a professor from Ternopil. In 2001, according to his Ukrainian Wikipedia page, he completed an internship at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC).

The UIUC’s Dmytro Shtohryn, or “Sadovyi,” also spoke about that “week of independence,” as someone who actually “witnessed the events of June 30, 1941 in Chortkiv, Ternopil Oblast.” In 1941, Shtohryn turned 18 years old. German troops occupied the small city of Chortkiv in early July, which had several thousand Jews. According to the website “My shtetl: Jewish towns of Ukraine,” in the coming days, “Ukrainians and Germans massacred about 300 Jews in the courtyard of the local prison.” At some point, there was a pogrom, likely led by Banderites. Who knows if Shtohryn might have participated?

During the war, the Shtohryn family provided shelter to members of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, the paramilitary arm of OUN-B that hunted Jews and waged a massive ethnic cleansing campaign against the Polish population in western Ukraine. In 1945, Dmytro turned 22, in Bavaria. He settled in a Displaced Persons camp in Augsburg, where the OUN-B created the first branch of the Ukrainian Youth Association (CYM, Спілки Української Молоді) and he became its president. At the time, the Banderites considered WW3 to be imminent, but the Cold War was just getting started. Dmytro Shtohryn arrived to the United States on a warship.

Shtohryn had also been an organizer in the scouting organization Plast, in which he made a group named after OUN founder Yevhen Konovalets (that still exists). By the early 1950s in Minnesota, he led a branch of “TUSM,” the radical student organization named after Mykola Mikhnovsky, who coined the slogan “Ukraine for Ukrainians!” The Banderite-led TUSM, another international organization, now defunct, included members of CYM and Plast, which were more or less rivals during the Cold War. To have been a prominent member of all three groups was a rare feat.

Shtohryn began his higher studies at the new Ukrainian Free University in Augsburg, which later relocated to Munich. By the end of the 1950s, he completed a master’s degree at the University of Ottawa, specializing in Ukrainian literature and writing a thesis about the poetry of OUN-M leader Oleh Olzhych. He also earned a bachelor’s degree in library science, and in 1960 started to work as a librarian at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Soon he discovered a passion for promoting Ukrainian studies. In 1964, he attended the first national meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies, and received credit as “one of the organizers of the American Library Association’s Slavonic Section.”

It didn’t take long for Shtohryn to get busy ordering Ukrainian publications for Urbana-Champaign. The director of the school’s new Russian, East European, and Eurasian Center (REEEC) supported his Ukrainization of their Slavic library. “Such centers were generously funded by the federal government and could to afford to buy even very expensive literature,” Shtohryn recalled in 2006. “When I arrived, the library had about 10,000 Slavic and Russian books. Today there are already almost 750-800 thousand of them. Among them … the library has about 70,000 Ukrainian publications in originals and microfilms.”

In the 1970s, Dmytro Shtohryn organized “TUSM alumni” and represented them in the U.S. executive board of the Mikhnovsky student association. He also became a full professor with academic tenure. Shtohryn subsequently got involved with the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute (HURI). He chaired a panel at one of their events in 1978. The following year, Shtohryn joined the Permanent Conference of Ukrainian Studies at HURI, made the first speech at a three-day HURI symposium, and led a Harvard conference featuring Soviet dissident Valentyn Moroz, who turned out to be not just a far-right nationalist but a Banderite attack dog in the Ukrainian community.

A month before OUN-B leaders Yaroslav and Slava Stetsko visited the White House in 1983, the UIUC held a conference on Ukrainian history. Dmytro Shtohryn chaired the organizing committee. In 1984 the UIUC launched a Ukrainian Research Program (URP) chaired by Shtohryn, to “function as an autonomous institution with its own executive committee, research advisory council, and associates.”

Starting in 1984, Dmytro Shtohryn co-organized an annual “Conference on Ukrainian Subjects” within the framework of the URP and an REEEC program. In the 1990s, these events turned into Ukrainian academic conferences, and the organizers made an effort to invite young scholars from Ukraine that used the Ukrainian language “at home, in schools and in their personal lives.” By the early 21st century, some up and coming OUN-B members in Ukraine (Volodymyr Viatrovych and Oleksandr Sych) even participated in these annual events. It was said that Shtohryn typically “carried the whole burden” of organizing them.

The 1985 Conference on Ukrainian Subjects was dedicated to World War II, and took place as the Department of Justice belatedly hunted for Nazi war criminals in the United States, with much of its focus on Ukrainian collaborators. The organizing committee included Taras Hunczak (1932-2024), a professor at Rutgers University. Hunczak, a former courier for the Ukrainian Insurgent Army at just 10 years old, was the editor in chief of a major monthly journal published by the Prolog Research Corporation—a CIA front group that I introduced in “Boychukgate.” Prolog was affiliated with an OUN faction of ex-Banderites led by Mykola Lebed, someone that the CIA shielded from prosecution. He ultimately passed the torch to Roman Kupchinsky, a Ukrainian American CIA officer.

In his memoir, Hunczak recalled that at the end of the Cold War, he accompanied the Prolog president (Kupchinsky) to a meeting with George Soros to propose that the billionaire’s foundation open an office in Kyiv. Soros allegedly shot down their proposal: “Ukrainians are antisemites.” Hunczak, a professional whitewasher of Nazi collaborators, was apparently just the man to convince him to give Ukraine a chance. Today, Ukrainian civil society activists (including far-right nationalists) are labeled “Sorosites,” because they are so dependent on grants from the Soros foundation and western-funded “non-governmental” organizations.

In 2003, the University Press of America published Ukraine: The Challenges of World War II, a collection of papers presented at the Conferences on Ukrainian Subjects. Taras Hunczak prepared the book with Dmytro Shtohryn. At least a few of the contributors (including Hunczak) were associated with Prolog. Myroslav Prokop, a former president of this CIA front group, worked as an editor at the OUN’s information bureau in 1930s Berlin. In mid-to-late 1944, he joined a “task force” that the OUN-B leadership in Ukraine dispatched “to establish contact with the Western allies,” according to historian Grzegorz Rossolinski-Liebe. Prokop wrote chapter 5: “Ukrainian Anti-Nazi Resistance, 1941-1944.”

Peter Potichnyj, allegedly the youngest fighter in the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), wrote chapters 6, 11, and 12. A 1966 memo by David Murphy, head of the CIA’s “Soviet Russia” division, said that “Potichnyj collaborated with a cover organization under one of our projects until 1961.” This was probably a reference to something connected to Prolog. According to historian Per Rudling, “Potichnyj was affiliated with the CIA.”

By the 1980s, a pair of North American UPA veteran societies—one affiliated with OUN-B, and the other with CIA-funded ex-Banderites—started to publish “Litopys UPA” (Chronicle of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army), a multi-volume “documentary history” of the Banderite paramilitary force.

During the Cold War, according to Rudling, this project was funded by the CIA, and Potichnyj was one of its directors. Meanwhile, the CIA and its Prolog crew smuggled thousands of pieces of literature to Ukraine, including texts such as “Litopys UPA” that romanticized the long defeated Banderite “liberation movement.” Some number of far-right Ukrainians in the 1990s were enchanted by the “forbidden history” of Ukrainian nationalism in the twilight of the Soviet Union. It’s unclear how effective the CIA was at reaching Soviet Ukrainians or planting the seeds of a nationalist revival in that period.

In the 21st century, the OUN-B has apparently inherited the Litopys UPA project with help from the Center for Research of the Liberation Movement (TsDVR). Dmytro Shtohryn was among the OUN-B leaders that co-founded this pivotal front group in 2002, not long after the rise of Andriy Haidamakha and the Center for US-Ukrainian Relations. That year, Shtohryn served on the steering committee of CUSUR’s main roundtable event. He did the same for the first one in 2000. The TsDVR put the Banderites at the front line of the memory war in Ukraine, and CUSUR helped put them on the map in Washington. “Sadovyi” had a hand in the creation of these OUN-B “facade structures,” which were both established at the dawn of the 21st century, when it seems that OUN-B was trying to win over new Western backers.

Volodymyr Viatrovych was the first TsDVR director until 2008, when he got put in charge of the Security Service of Ukraine archives. He was trusted with the new Banderite center at the age of 25 years old. In 1999, Viatrovych led a special summer camp dedicated to the memory of Stepan Bandera. In 2003, when Hanczuk and Shtohryn’s “Challenges of World War II” book came out, the new TsDVR director took part in that year’s Conference on Ukrainian Subjects.

During the “Orange Revolution” in Ukraine (November 2004 - January 2005), Dmytro Shtohryn chaired the OUN-B “Land Leadership of America,” and Viatrovych got involved with the “Pora!” youth group. (After they split in 2005, Viatrovych became a leader of “Black Pora.”) Olga Onuch, a professor of Ukrainian politics at the University of Manchester, cited Viatrovych when she wrote about the first “Maidan revolution,”

the [historical] OUN is highly respected among many Ukrainian activists for their ability to activate and coordinate a complex network of related SMOs [Social Movement Organizations] in different regions of Ukraine, for their defence of Ukrainian language and culture, but not for their use of violent tactics. Viatrovych explained, “the influence of the OUN…on activists today is undeniable…we even used some of their organizational techniques, of ‘sotky’ when we coordinated activities in 2003/04, but we adhered to non-violent repertoires guided by liberal values.”

After the victory of the “Orange Revolution” — a presidential election do-over in which the pro-western candidate Viktor Yushchenko defeated the “pro-Russian” Viktor Yanukovych, putting the first ally of the “Bandera Lobby” into power — the State Department started to fund the OUN-B’s Ukrainian Youth Association in Ukraine via the U.S. Agency for International Development. Meanwhile, a Waffen-SS veteran (Orest Vaskul) chaired the OUN-B “Land Leadership in Ukraine.” By this point, lingering public criticism of the Banderites from the Prolog crowd seems to have dissipated. Perhaps the annual conferences organized by Dmytro Shtohryn and Walter Zaryckyj put their minds at ease.

In the spring of 2007, a large part of the Prolog archives — more than 10,000 pages of documents that belonged to Mykola Lebed, Bandera’s wartime deputy and postwar CIA-backed rival — were transferred to the Center for the Research of the Liberation Movement in Lviv. The TsDVR came to an agreement with Petro Sodol, another young UPA veteran affiliated with Prolog and “Litopys UPA,” who also fought in Vietnam. He presented a “paper on the Ukrainian Insurgent Army in Soviet sources” at the 1989 Conference on Ukrainian Subjects, which featured some speakers affiliated with the U.S.-funded Ukrainian outfits, Prolog and Radio Svoboda. By 2007, Litopys UPA worked with the State Archive of the Security Service of Ukraine.

To celebrate the fake 65th anniversary of the UPA and the 100th anniversary of the birth of UPA leader Roman Shukhevych, in 2007 the TsDVR prepared a “unique photo exhibit about the UPA, consisting of 22 banners (approx. 6 by 2.5 feet), with nearly 500 photos showing its history.” The U.S. premiere of this exhibit took place over the Fourth of July weekend at the Banderite summer camp in Ellenville, New York, which has larger than life busts of Bandera and Shukhevych as part of its “Heroes’ Monument.” According to the Ukrainian Weekly newspaper, “This photo exhibit will also be shown at various universities, the United Nations, the U.S. Congress, major libraries, as well as other locations in order to acquaint the broader public with the history of the UPA.”

In New York City, Bohdan Harhaj chaired an “All-Community National Committee” to commemorate the 65th UPA and 100th Shukhevych anniversaries. Harhaj led the Ukrainian American Youth Association, which owns the Banderite camp in Ellenville, New York, and he also chaired the OUN-B “Land Leadership of America” (after Shtohryn). The events in Manhattan included a conference at the Shevchenko Scientific Society featuring Taras Hunczak, Peter Potichnyj, and Dmytro Shtohryn, and a presentation of the TsDVR photo exhibit (“UPA — The Army of Immortals”) at the Ukrainian Museum. According to the Ukrainian Weekly, “The All-Community National Committee has undertaken efforts to display the photographs in the U.S. Congress, military academies and universities.”

Later that year, Yushchenko posthumously awarded the “Hero of Ukraine” title to Roman Shukhevych, a Nazi collaborator and major ethnic cleanser. This might have been the ultimate goal of the Banderites when they prioritized the UPA and Shukhevych anniversaries in 2007—to put pressure on the president to follow through with this controversial decision, and/or to lay the groundwork for him.

After Volodymyr Viatrovych became the director of the State Archive of the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU, Sluzhba Bezpeky Ukrayiny), this agency launched a website, or “Digital Archives Center,” including online collections of documents about the OUN, UPA, and the 1932-33 “Holodomor.” Viatrovych also chaired a working group that the SBU established “to study the activities of the OUN and UPA,” and he served as an advisor to SBU director Valentyn Nalyvaichenko, a friend of the Banderites who participated in numerous CUSUR conferences.

By 2009, when Ukrainian nationalists commemorated the 100th anniversary of Stepan Bandera’s birth, and the 50th anniversary of his assassination, the first director of the state-run Institute of National Memory reportedly “tasked his colleagues to restore the good name of Stepan Bandera.” (His deputy, Roman Krutsyk, was a prominent OUN-B member.) Volodymyr Viatrovych said that “the logical move … would be granting him the Hero of Ukraine title.” The Banderites got their wish shortly before Yushchenko left office in 2010, after he failed to even reach the second round of the presidential election.

It was in 2009 that the SBU and TsDVR turned a former prison in Lviv into a nationalist museum. The SBU owned (and technically managed) the building, with the main office of the TsDVR located upstairs. Although Ukrainian nationalists and Nazis killed Jews here in 1941, at the Banderite-run Lonsky prison museum, “Jewish suffering is omitted.” In a 2015 essay about the museum, the historian John-Paul Himka called it “a place where Jewish memory is erased as well as the memory of crimes against Jews perpetrated by Ukrainian nationalists.”

The museum exhibition glides lightly over the Nazi occupation. The little it has to say highlights the suffering of OUN members. The information for visitors has nothing at all to say about the persecution of Jews at Lontsky St. prison during the war, although a small amount of information is available on the museum website. Most important, the museum glorifies OUN without mentioning or admitting that the militia associated with OUN was deeply involved in murders and other atrocities against Jews on the very premises of the Lontsky St. prison and in the other Lviv prisons in July 1941.

Himka went on to write,

The museum’s presentation of history, which is at variance with the results of professional historical research, is able to be sustained not only because of regional support in Ukraine and formerly because of Ukrainian government patronage, but also because of a strong and mutually reinforcing alliance with OUN in the North American diaspora. The nationalists in the diaspora use their connections with and influence upon ethnic academic outposts, Canadian politicians, and the press to reinforce the message of the Lontsky St. museum and to make deflective Holocaust negationism appear respectable.

Himka also noted that the museum displayed (“with little to no commentary”) antisemitic newspaper clippings from the Nazi collaborationist Ukrainian press — including one about Dmytro Shtohryn’s hometown of Chorktiv.

Another clipping narrated that in Chorktiv the NKVD arrested many Ukrainians immediately after the outbreak of the German-Soviet war on the basis of denunciations by "local Jewish communists." "To give the complete picture, it must be pointed out that after the NKVD fled from Chortkiv Jewish-communist squads spent an additional three days rampaging in the city, shooting at the innocent population and sowing terror right and left."

At that year’s 26th (and final) Conference on Ukrainian Subjects, the Ukrainian Jewish poet Moisei Fishbein presented a paper on “The Jewish Card in Russian Special Operations Against Ukraine.” Per Rudling has described Fishbein one of “the most successful popularizers of the nationalists’ narrative, denying the UPA’s anti-Jewish violence.” Among other things, Fishbein (and the TsDVR) promoted the fraudulent autobiography of a fictitious Jewish woman, I Am Alive Thanks to the UPA. In his 2009 speech at Dmytro Shtohryn’s conference, Fishbein also claimed that Roman Shukhevych and his wife saved a Jewish girl during the Holocaust. His speech became a favorite “scholarly” source for Ukrainian nationalists to cite, such as Volodymyr Viatrovych when he argued that “generally there are many proofs to show that Ukrainian nationalists provided help and shelter to persecuted Jews.”

What the historian Georgiy Kasianov has called Ukraine’s “internal memory war” heated up in 2010, starting with Yushchenko’s parting shot: the Hero of Ukraine award for Stepan Bandera. Not long after Yushchenko left office, and his “pro-Russian” rival Yanukovych replaced him, the Donetsk District Administrative Court overturned the outgoing president’s controversial declaration. It soon did the same for Shukhevych’s Hero of Ukraine title. In the meantime, the new Education Minister became a boogeyman of the Banderites. As Kasianov wrote in his 2022 book, Memory Crash: Politics of History in and Around Ukraine, 1980s–2010s,

The new minister, Dmytro Tabachnyk, was well known for his negative attitude toward nationalized history and for his loyalty to the Soviet nostalgic version. He gleefully shocked the public with his statements and appraisals of the past in which he denounced and ridiculed Ukrainian nationalism. In an April 2010 interview with the BBC, he declared that the textbooks of Ukrainian history are written from an ethnocentric position and must, therefore, be revised and rewritten from an anthropocentric position. … Tabachnyk used his position to publicly criticize the national/nationalist memory narrative and largely contributed to the development of the internal memory war in Ukraine.

In September 2010, after a change in the leadership of Ukraine’s internal security service, the SBU briefly detained one of its own employees, Ruslan Zabily, the former TsDVR director who ran the Lonsky prison museum. “Over the next week, Zabily became probably the most popular figure in news feeds and on political talk shows,” according to Kasianov. “Latest on Ukraine’s history wars: Orange fighter down,” reported openDemocracy. “SBU under fire for using KGB-style tactics,” said the Kyiv Post. Volodymyr Viatrovych was apparently also ousted from the SBU, after which he became a research fellow at the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute to familiarize himself with its portion of the Mykola Lebed (Prolog) archives. The Banderite memory warriors would be back with a vengeance after the next “Maidan revolution.”

In 2014, Dmtryo Shtohryn’s chairmanship of the UIUC Ukrainian Research Program ended and it was replaced with a Ukrainian Studies Program. Meanwhile, OUN-B member Serhiy Kvit, an enthusiast of the fascist ideologue Dontsov, had replaced Dmytro Tabachnyk as the Education Minister. Five years later, as the president of the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy (NaUKMA), Kvit mourned the death of Shtohryn, “the librarian of the Ukrainian movement” and an “honored member of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists.”

The polemical context of Prof. Shtohryn’s annual conferences, ongoing lively discussions and exchanges of thoughts and ideas were vitally important for Ukrainian intellectual life. The meetings focused on different topics: the participants discussed the future of Ukraine and the Ukrainian diaspora, presented the results of sociological research, discussed various issues of Ukrainian academic and political life, as well as topics of history, literature, the arts and economy. At one of these conferences, Viacheslav Briukhovetsky presented his project to revive the Kyiv Mohyla Academy, which was later successfully implemented and today is the National University of Kyiv Mohyla Academy.

Serhiy Kvit said they first met in 1995, when he studied at the Ukrainian Free University in Munich, and Shtohryn lectured there. According to Kvit, “We immediately began to communicate not only as a student and professor, but also as people who want to change something in this life. In particular, we collaborated on the journal Ukrainian Problems (1991-2003), founded by the late Zinoviy Krasivsky. To support the journal, Prof. Shtohryn engaged Ukrainian scholars from the United States and Canada. In parallel, Prof. Shtohryn co-founded the Center for Liberation Movement Studies headed by Volodymyr Viatrovych.”

Krasivsky was the OUN-B “Land Leader in Ukraine” at the time of independence, who co-founded the far-right nationalist party “State Independence of Ukraine.” In the 1990s, Kvit joined the paramilitary organization “Tryzub” named after Stepan Bandera, which the OUN-B established. According to the Ukrainian media outlet Zaborona, “Since its inception, ‘Tryzub’ activities have been closely linked with the Security Service of Ukraine and specifically with its future head Valentyn Nalyvaichenko.” The OUN-B’s break-up with Tryzub might have been a precondition for turning over a new leaf in Washington at the turn of the 21st century. Ex-Prolog associate Taras Kuzio (from England, which he described as an “OUN-B stronghold”) even wrote a pair of letters to the editor of New Jersey’s Ukrainian Weekly newspaper in 2001, seeking clarity about the OUN-B’s relationship with Tryzub.

In the spring of 2019, about four months before Shtohryn died, the Maidan Museum in Kyiv hosted the first TsDVR congress since December 2013. Volodymyr Viatrovych and Serhiy Kvit joined Ivan Patrilyak, the Banderite dean of history at the Taras Shevchenko National University in Kyiv, to make “guest” speeches. The alleged “Land Leader in Ukraine” read some words from OUN-B’s international chairman Stefan Romaniw in Australia. Steve Bandera, the Canadian grandson of you-know-who, brought greetings from their friends at the Ucrainica Research Institute in Toronto, another OUN-B front, which is a co-owner of the Banderite headquarters in Kyiv.

Reports summarized the work of the OUN-B memory warriors since the “Revolution of Dignity,” such as Andriy Kohut, who remains the director of the SBU archive almost five years later. On February 24, 2022, Kohut lectured students at the University of Illinois Chicago on memory politics in Ukraine. “The fact that Putin mentioned decommunization in his speech before the invasion confirms that Russia is very afraid and tries to avoid the path of rethinking the Soviet past that Ukraine has chosen,” Kohut later told the U.S.-funded Radio Svoboda.

Last year, Lubomyr Luciuk, the Canadian co-editor of Enemy Archives, and a professor at the Royal Military College of Canada, said at a New York City conference organized by the Banderites that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine gave them “the best chance ever to tell our story … so now is the time for us to win the memory war.” His co-editor’s wife recently complained that the American Library Association retracted its award for their book after “one article by a pro-Russian author.” Around that time, Luciuk gave an interview to promote his book, and said that Stepan Bandera’s son, Andriy, “got me interested in writing” after they met in Canada.

In April 2024, Ottawa Citizen journalist David Pugliese reported, “American Library Association pulls award for RMC professor’s book” after “a Jewish organization and Holocaust scholars … raised concerns it whitewashes Nazi collaborators in Ukraine.” Pugliese noted that Luciuk’s co-editor, Volodymyr Viatrovych, “shared a social media response in which a Ukrainian pointed out that [Lev] Golinkin is a Jew and a parasite. That same account also accused another Ukrainian Jew, who has spoken out about the history of Nazi collaborators, of being a parasite.” Pugliese was referring to posts by Daria Hirna, who doesn’t appear to be an OUN-B member, but is a former TV presenter that became the new director of the OUN-B’s Center for Research of the Liberation Movement in December 2021.

Chris Alexander, the Conservative politician who recently smeared Pugliese as a Soviet/Russian agent and claimed to substantiate his accusations with Ukrainian KGB documents, might have had some help from the editor(s) of Enemy Archives. Last year, Alexander promoted a National Post op-ed from Lubomyr Luciuk, which was really an excerpt from his new book with Viatrovych. Luciuk emphasized that before invading Ukraine, Vladimir Putin “specifically referred to Banderivtsi, members of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) headed by Stepan Bandera,” and says that “we certainly did not anticipate this … being deployed as an excuse for starting a large-scale war in 21st-century Europe.”

The Centre for Strategic Communication and Information Security, a Ukrainian government organization established by the Ministry of Culture and Information Policy, weighed in on the ALA scandal two days before Pugliese’s article: “How Academic Freedom and Ukrainian History are under attack, on the example of one dirty campaign.” This government organization blamed that “part of the Western academic environment, which consistently promotes the thesis about ‘Ukrainian Nazism’.” According to this “leading channel of government communication about the war in Ukraine,”

In reality, there are no testimonies and documentary evidence that would confirm the cooperation of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) with the Nazis in the mass murder of Jews. … There is also no confirmation of the words that the Ukrainian Insurgent Army as an organized force participated in the murder of Jews. … Unfortunately, the KGB special operations gave results, and now the history of the Ukrainian national liberation movement became one of the most mythologized pages of the Ukrainian history.

The Centre for Strategic Communication also took aim at Ukrainian Jewish leader Eduard Dolinsky, who I’m guessing is the other person that Daria Hirna called a “parasite.”

Special attention should be paid to Golinkin’s references to Eduard Dolynskyi, who presents himself as the head of the “Ukrainian Jewish Committee”, but does not really represent the Jewish community of Ukraine. Instead, he is well known for spreading fakes about the growth of antisemitism in Ukraine and the glorification of Nazism.

I agree that “part of the Western academic environment” deserves more blame for the memory war, as a result of which the history of World War II “became one of the most mythologized pages of Ukrainian history,” and far-right nationalists are increasingly empowered as Ukraine’s thought police.

Thanks for reading. If you want to support my work, you can “Buy Me a Coffee.”