Australia bid farewell to a 'leading light of our proudly multicultural nation'

WSWS: 'Australian Labor Party holds state funeral for global Ukrainian fascist leader'

Stefan Romaniw, the former OUN-B leader (2009-22) from Melbourne, Australia, died unexpectedly in Poland over a month ago, which came as devastating news for Banderites around the world and Romaniw’s many allies, including government officials in Australia. The posthumous praise for Romaniw reached Orwellian levels, for example when Prime Minister Anthony Albanese hailed the Ukrainian nationalist leader’s inspirational “commitment to the cause of peace.”

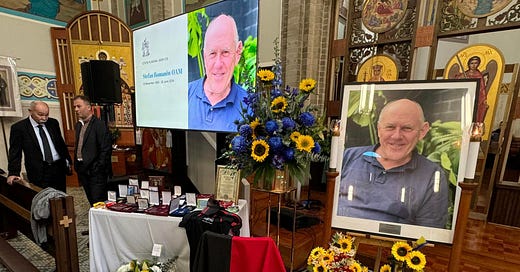

On the second Friday of July, flags were flown at half-mast in Romaniw’s home state of Victoria, and its government held a state funeral for him at the Ukrainian Catholic church in North Melbourne. Representing the Prime Minister was Bill Shorten, the Minister for Government Services and former leader of the Labor Party, which also governs in Victoria. “We still seek his wise counsel,” Shorten said at the funeral. “The urge is still there to seek the vague approval from the charismatic leader.”

According to the Australian Federation of Ukrainian Organisations (AFUO), which Romaniw led since the 1990s, “His huge impact — as an untiring community leader, patriot, warrior, mentor and friend — was unmatched. His skill as a collaborator, mediator and unifier strengthened our community immeasurably. Upon his broad shoulders our community grew and prospered, and weathered many storms. He was for so many of us a Ukrainian-Australian hero — a true legend.” The AFUO even declared, “There will never be a person of whom we were so proud.”

Stefan Romaniw acknowledged that the OUN-B operates “through its various facades and partner structures,” meaning its various front groups and other organizations in which the Banderites exercise considerable influence, typically after many years of entryism. For example, the Stepan Bandera National Revival Center is a “facade structure that is essentially synonymous with the OUN-B leadership in Ukraine and its headquarters building in Kyiv, which is located a short walk from the headquarters of the Security Service of Ukraine, and also close to the “Maidan,” or Independence Square. The AFUO is an important “partner structure” in Australia that functioned as a de facto OUN-B front under Stefan Romaniw’s decades-long stewardship.

“Tactics change, means and methods are updated,” according to Romaniw, but “Ukrainian nationalism as an ideology and political movement is fundamentally based on unchanging values.” For him, this meant honoring the 20th century ideologues of Ukrainian fascism, such as Mykola Mikhnovsky, Dmytro Dontsov, Stepan Bandera, Yaroslav Stetsko, and Stepan Lenkavsky, and adapting modern strategies to advance their catastrophic agenda in the 21st century.

In 2009, the new OUN-B leader from Australia told the Youth Nationalist Congress, a militant Banderite facade structure in Ukraine, that “it is necessary to educate new Banderas.” A couple years later, Romaniw said at a conference in Washington, “Although the Ukrainian people may be ready or may become soon ready for another attempt at revolutionary change … an alternative national elite is not yet in place to take over state power.”

By 2013, his Organization made preparations to seize the moment. In the following year, OUN-B members took over the Ministry of Education, the state-run Institute of National Memory, and important functions in the Security Service of Ukraine, in particular its immense archives. These were not just random corners in the halls of power. Under Romaniw’s leadership, the OUN-B escalated Russia and Ukraine’s “memory war,” which obviously contributed to the ongoing cataclysm.

According to Mykhailo Ratushny, an OUN-B member who chaired the Kyiv-based Ukrainian World Coordinating Council in recent years, “you can already say that [Stefan Romaniw’s] leadership in the nationalist [OUN-B] movement was on par with figures such as Stepan Bandera and Yaroslav Stetsko.” This is certainly true, if only in terms of longevity. In the middle of his second term as Providnyk, Stefan Romaniw boasted that the extremist “ideas of Mikhnovsky, Bandera, Dontsov, Stetsko, Lenkavsky and other ideologues of Ukrainian nationalism have been very acutely and distinctly actualized today.”

In order to understand how Romaniw became a “towering figure” in the Ukrainian diaspora, a “leading light of our proudly multicultural state and nation” (according to Jacinta Allan, the Premier of Victoria), and an influential chieftain of a far-right nationalist movement in Ukraine, who dedicated his life to stoking the flames of a suicidal conflict with Russia, first it is necessary to recount the rise of this unique Banderite, also known as “Bereza” (Birch) in the OUN-B.

In spite of going bald at a young age, Stefan Romaniw steadily rose through the ranks of the Ukrainian Youth Association (CYM), an international OUN-B front group. He practically spent his entire life in this organization, which grooms young Banderites around the world. At just 25 years old, Romaniw started to run the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Saturday school in North Melbourne. He spent 17 years as its principal, including a decade as the Australian president of CYM, and emerged as a “leading light” of the OUN-B in Australia.

After World War II, during the period in which Romaniw’s parents met in Germany and moved to Australia, the OUN-B established the Ukrainian Youth Association, which according to historian Per Rudling, alarmed some officials in the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. They feared that the Banderites wanted “to create a small army on its own after the style of the Hitler Youth.” Romaniw’s German mother Maria (1927-86) came from Stuttgart and presumably went through the League of German Girls, the female wing of the Hitler Youth. Apparently she was unbothered by any parallels that she noticed with CYM, the “Bandera Youth,” including its uniforms. According to Romaniw, she “never saw bad in anything. On the contrary, she would always try and spin a good story.”

Maria Romaniw died in 1986. Later that year in Munich, the birthplace of Nazism and site of the OUN-B headquarters during the Cold War, her son delivered the “words of farewell from Ukrainian youth,” who “came to love you as a father,” at the funeral of OUN-B leader Yaroslav Stetsko — and over four decades earlier, the short-lived “Prime Minister” of a pro-Nazi regime, at least on paper, in German-occupied western Ukraine. “Standing at your graveside, we make this sacred promise,” vowed Romaniw. “You, our unforgettable friend, are leaving behind people of the younger generation who aspire to accomplish your unfulfilled earthly mission.” For those unfamiliar with his hero Yaroslav Stetsko, here is an excerpt from Per Rudling’s new book, Tarnished Heroes: The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists in the Memory Politics of Post-Soviet Ukraine.

Possibly the most intelligent of the OUN leaders, Stetsko was certainly one of the most radical, and his role in the radicalization of the Galician OUN cannot be overstated. ... In 1938 Stetsko denounced democracy 'as a corruption of morality... . The rule of money is absolute, and the financial bourgeoisie, Masonry, and a clique of international criminals led by Jews control governments.' In May 1939, Novyi Shliakh, the leading OUN paper in Canada, published Stetsko's article 'We and Jewry,' penned under his pseudonym Zynovyi Karbovych, in which he characterized Jews as 'nomads and parasites,' a nation of 'swindlers, materialists, and egoists,' interested only in 'personal profit,' who found 'pleasure in the satisfaction of the basest instincts,' and determined ' to corrupt the heroic culture of warrior nations.' Stetsko further elaborated on the issue of separation of Jews from Ukrainians. He argued that Ukrainians constituted 'the first people in Europe to understand the corrupting work of Jewry,' which, according to Stetsko, was the reason why they had separated themselves from the Jews for centuries, something which, in turn, had enabled them to retain 'the purity of their spirituality and culture.' ... Stetsko was of the opinion that the 'minority question' in Ukraine would be solved by means of the minorities ceasing to exist. He envisioned three paths to achieve that goal: assimilation, deportation or 'physical measures,' proposing the setup of ghettos, even though he felt that the ideal solution to the Jewish question would be the deportation of all Jews from Ukraine to the far east.

Also in 1986, the Australian association of Banderite veterans from the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) published a monstrous 110 page screed against “Jewish Bolshevism” titled Why is One Holocaust Worth More Than Others? “Holocaust propaganda is so effective in brainwashing people,” a major Australian Holocaust denier (John Bennett) wrote in Part B of the appendix, “that revisionist historians who claim there was no plan to exterminate Jews, there was no mass gassings and that fewer than 1 million Jews died of all causes during World War II are persecuted, and their books banned by trade boycott.”

The society of UPA veterans was a pillar of the “Organizations of the Ukrainian Liberation Front,” the above-board coordinating body of OUN-B facade structures. In Australia, the “Front” came under the leadership of Stefan Romaniw by 1990. He was already the president of the Association of Ukrainians in Victoria, and soon the chairman of its parent body, the AFUO, which included the UPA and Waffen-SS veteran societies as member organizations. Undoubtedly, there were extremists and probably war criminals among their ranks, especially the Banderite “insurgents” who hunted Jews in the forests of western Ukraine and perpetrated a massive ethnic cleansing campaign against Poles. Romaniw shared their sensitivity to the hunt for Nazi war criminals in Australia, and any suggestion that Ukrainian nationalists participated in the Holocaust.

“Mark Aarons was spreading the same thing about OUN, UPA, the CIA, and the Cold War,” ranted Walter Zaryckyj, an up-and-coming U.S. Banderite leader, in his 1989 “Magic Circle” speech to Canadian members of the Ukrainian Youth Association. The Banderites resented Aarons, because as the Australian Broadcasting Corporation explains, “Despite threats against him, it was his reporting for the ABC during the 1980s that prompted the War Crimes Amendment Act of 1988. His work also led to the creation of the Special Investigations Unit (SIU).” But only one person, an old Ukrainian man, was tried under the war crimes act, and the Nazi-hunting SIU failed to convict him. According to Mark Aarons, the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation recruited former Nazi collaborators and “put them on their payroll as agents in their anti-Communist war.” What about the Banderites?

In the years to come, a bizarre scandal rocked Australia, after a novel about a Ukrainian family that collaborated with the Nazis made its pseudonymous author the youngest winner of one of the most prestigious literary awards in the country. As it turned out, “Helen Demidenko” lied about her Ukrainian ancestry, and her book was slammed as an antisemitic hoax. ABC contributor Philip Mendes contrasted Helen Dale, the real author of The Hand that Signed the Paper, with John Bennett, the aforementioned Holocaust denier: “Demidenko did not deny the Holocaust occurred, but attempted to justify it by presenting a contemporary version of the age-old Judeo-Communist thesis which had been used by anti-Semites throughout the first half of the twentieth century as a rationale for genocide.”

As Mendes recalled, “Demidenko’s viewpoint provoked enormous public debate that continued for over 12 months.” Before “Demidenko” was exposed as non-Ukrainian, AFUO president Stefan Romaniw came to her defense. Later, he agreed to a meeting with the Executive Council of Australian Jewry, and Romaniw reportedly accepted “Ukrainian responsibility for participation in the Holocaust.” In reality, he “endorsed” a 1991 speech by Leonid Kravchuk, soon to be the first president of Ukraine, in which “the [Soviet] authorities admitted publicly for the first time that most of the victims at Babyn Yar were Jews.” Romaniw was diplomatic, but not as compromising as many now remember. In his memoir, Understanding Ukraine and Belarus, historian David Marples recalled meeting Romaniw in 2010. The new OUN-B leader “wanted to arrange a breakfast so that he and some colleagues could question me about [Stepan] Bandera. I had met Romaniw a year earlier at a conference in Adelaide, and though friendly, he had struck me as one of the more fanatical nationalists in the community.”

With Romaniw already at the helm of the AFUO in the 1990s, it is unsurprising that it served as a “partner structure” of the Banderites, and he allegedly played a role in the establishment of Australian-Ukrainian relations, for example, the opening of a Ukrainian embassy in 2003. In the meantime, Stefan Romaniw became an “adviser on ethnic affairs” to the Australian premier John Howard, and the chairman of the Ethnic Communities Council of Victoria, “the peak body for our state’s migrant and refugee communities.” Before Howard served as Prime Minister (1996-2007), he spoke at the 1989 conference of the far-right World Anti-Communist League in Brisbane, which Stefan Romaniw would have never missed as the new chairman of the “Ukrainian Liberation Front” in Australia.

In 2001, Stefan Romaniw was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia for “service to education and language learning.” A couple years later, he received the Australian Centenary Medal, and in 2004, the Victorian premier further honored Romaniw with his appointment as an Australia Day Ambassador. It would be ironic if this glory from the state propelled Romaniw to the top of the clandestine OUN-B. He probably joined its international leadership by 2005, when Andriy Haidamakha started his second term as Providnyk, or “Leader.”

The Senate of Australia gave Romaniw an important victory in 2003, when “after heavy lobbying by Australia’s Ukrainian community,” it recognized the “Holodomor,” or 1932-33 famine in Soviet Ukraine, as “one of the most heinous acts of genocide in history” which killed “an estimated 7 million Ukrainians.” (This “estimate” roughly doubled the millions of victims.) In 2005, under the leadership of OUN-B member Askold Lozynskyj from New York, the Ukrainian World Congress put Romaniw in charge of its International Coordinating Committee for Holodomor Awareness and Recognition. That turned out to be a lifetime appointment. In this capacity, Stefan Romaniw started to work closely with the Ukrainian government. Apparently, the third president of Ukraine (Viktor Yushchenko, 2005-2010) adopted the memory politics of his Banderite wife from Chicago. As told by historian Georgiy Kasianov in his 2022 book, Memory Crash: Politics of History in and around Ukraine, 1980s–2010s,

It is well known that Viktor Yushchenko, who was well informed about the numerous and diverse studies of historians and demographers of the 2000s, chose to ignore their data and insisted that the total number of Holodomor victims amounted to seven to ten million people. The source of his inspiration is no secret: it was actively defended by the “nomenklatura” of the Ukrainian diaspora, in particular the leadership of the Ukrainian World Congress (UWC). The June 1, 2008 report of the International Coordination Committee of the UWC headed by Stefan Romaniw, the leader of the OUN (Bandera faction), clearly contained the figure of seven to ten million victims, which was to be promoted to the presidential secretariat and the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory. The victimhood competition evolved in the context of a political situation in which the formula “seven to ten is greater than six” played an important role. Stanislav Kulchytsky recalled, that the head of the World Congress of Ukrainians Askold Lozynskyj insisted on 7–10 million simply because it is bigger than 6 million, the number of Jews who perished during Holocaust. Lozynskyj in turn suggested that Kulchytsky and his followers deliberately reduce the number of Holodomor victims to avoid competition with the Holocaust. The very term “Holocaust” was appropriated. During the period of active build-up of the cultural memory of the Holodomor, the famine of 1932–33 was quite often called the Ukrainian Holocaust. It should be mentioned that this pattern of manipulation of the figures was not appropriated even by the majority of supporters of the genocidal version of Holodomor in Ukrainian academia.

During Yushchenko’s presidency, Romaniw received all three classes of the Ukrainian Order of Merit, mainly for his “Holodomor” activism. In late 2007, Romaniw visited Yushchenko at his presidential residence to discuss the “year of global activities” planned for 2008 to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the famine. This included a global relay of the “International Holodomor Remembrance Flame,” also known as the “Ukrainian Genocide Torch,” which the Banderites largely spearheaded. The rising OUN-B leader also worked with the Foreign Ministry and the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU), and singled out Valentyn Nalyvaichenko, the nationalist SBU director under Yushchenko, as someone who “has proven to be a true leader on these issues, certainly setting the pace.”

With powerful friends in Ukraine, Stefan Romaniw became the Secretary General of the Ukrainian World Congress in 2008. Meanwhile, Volodymyr Viatrovych was put in charge of the SBU archives, and relinquished his duties as the director of an important OUN-B front in Ukraine, the “Center for Research of the Liberation Movement,” which started to work out of a problematic museum in Lviv — staffed by Banderites, but managed by the SBU. It was during this period, as the SBU and OUN-B grew closer in the Yushchenko years, that Stefan Romaniw emerged as a leader of the Ukrainian diaspora, and ascended the Banderite throne in 2009.

The next installment of this series will recap Romaniw’s tenure as OUN-B leader. Part Three will revisit his death and the Orwellian celebration of his life. From there, we’ll move on to OUN-B’s efforts to revive the Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations, and other updates on the “Bandera Lobby.” If you want to support my work, you can “Buy Me a Coffee.”

Yes it's been War Criminals Welcome in Australia.

That's a huge book by Mark Aaron's, and out of print. I've seen it second hand for as much $2000 + however I found on Internet Archive to read for free.

Well, Victorian goverment plans to name some street or place by name of multicultural leader Stefan Romaniw.

Bandera street we already have;)