Note to subscribers: Substack says this is too long for some to read as emails.

A decade ago, after a (relatively short-lived) breakthrough in parliament, the Svoboda party was the internationally infamous Ukrainian far-right organization. However, by 2014, it apparently flew too close to the sun, and was eclipsed in notoriety by the extremist Right Sector, which soon enough became old news with the rise of the neo-Nazi Azov movement. Now we’re told that Azov is nothing to worry about.

Svoboda, like Azov, grew out of Ukraine’s marginal neo-Nazi movement of the 1990s: the Social-National Party of Ukraine (SNPU) and its paramilitary arm, Patriot of Ukraine. The SNPU, a political party, became Svoboda in 2004 and essentially rebranded as Banderite. Svoboda tried to disband Patriot of Ukraine, but it was revived in Kharkiv, where it ultimately spawned the Azov movement.

According to political scientist Ivan Katchanovski, the Svoboda party “regards itself as an ideological successor of the OUN,” or the fascistic Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists. Svoboda united members of both the Banderite (OUN-B) and Melnykite (OUN-M) factions of the OUN, as well as “social nationalists” from the SNPU, including neo-Nazi football hooligans.

At least some of Svoboda’s neo-Nazi elements have since migrated to Azov. In his 2012 essay on “The Return of the Ukrainian Far Right,” historian Per Anders Rudling noted that Svoboda’s antisemitic leader Oleh Tyahnybok “undertook significant efforts to remove the extremist image… Presenting Svoboda as the successor of Dontsov and the OUN, Tiahnybok regards Svoboda as ‘an Order-party which constitutes the true elite of the nation.’”

In my opinion, the Svoboda party is crypto-Nazi, whereas the Banderites remain Nazi collaborators. In 2014, at the dawn of the “Ukraine crisis,” The Nation interviewed journalist Russ Bellant about “this unexamined fascist element.”

The element has a long history, of a long record that speaks for itself, when that record is actually known and elaborated on. The key organization in the coup that took place here recently was the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists [OUN], or a specific branch of it known as the Banderas [OUN-B]. They’re the group behind the Svoboda party, which got a number of key positions in the new interim regime.

In the past year Azov fighters have been fully welcomed into the Banderite pantheon of “Heroes,” and a former OUN-B “facade structure” launched Right Sector in 2013, but the Svoboda party in particular appears to have (perhaps always had) a special relationship with the Bandera Organization.

Since 2009, Viktor Roh has been the editor in chief of the OUN-B’s weekly newspaper, “Path of Victory.” He joined the political council of the new Svoboda party in 2004. It’s unclear how long Roh remained in that position, but he was already a notable representative of OUN-B as the inaugural leader of its Youth Nationalist Congress, established in 2001.

For years, a pair of deputy chairmen of the Svoboda party have been regular contributors to “Path of Victory.” That would be Oleksandr Sych, the deputy chairman for ideological issues, and Yuriy Syrotiuk, the chief of political education. Both appear to be notable members of OUN-B.

Oleksandr Sych managed OUN-B leader Slava Stetsko’s first parliamentary campaign, and spent weeks by her side. Stetsko led the OUN-B from 1991-2001 and its political party (“Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists”) from 1992 onwards. In 2002, a year before she died, Sych organized a volume of writings by Stepan Lenkavsky (1904-1977) on behalf of the OUN-B’s Stepan Bandera Center for National Revival (CNR). Lenkavsky, an OUN-B propagandist who wrote the “Ten Commandants of the Ukrainian Nationalists” and succeeded Bandera after his 1959 assassination by the KGB, once said during World War II, “regarding the Jews, we will adopt any methods that lead to their destruction.” In recent years, Sych founded the “Institute for Scientific Studies of Nationalism,” both of which are rather obsessed with Lenkavsky.

At some point, presumably in the 2000s, Sych apparently served as the first deputy chairman of OUN-B, at a time when its point person in Ukraine was a veteran of the Waffen-SS. By 2006, Oleksandr Sych became the deputy chairman of Svoboda for ideological issues and its leader in the Ivano-Frankivsk region. Two years later, the Banderite CNR, directed by Sych, hosted a round table to unite Ukraine’s far-right “national-patriotic forces” ahead of parliamentary elections. Speaking at this event, another deputy chairman of Svoboda argued that their party was the most likely to enter parliament and observed that it had already united “prominent representatives” of the OUN-B and OUN-M, naming Oleksandr Sych and the Melnykite leader.

Svoboda’s breakthrough on the national level arrived four years later, by which time Sych had served two years as the head of the Ivano-Frankivsk oblast council, or regional parliament. This body declared 2012 to be “the Year of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army,” after the OUN-B leadership dedicated 2012 to Lenkavsky’s commandant: “Remember the great days of our liberation struggle.” In the coming weeks, Svoboda mobilized against historian Grzegorz Rossolinski-Liebe, working on the first scholarly biography of Stepan Bandera. As Open Democracy put it, Svoboda “employed threats of violence to cancel a series of public lectures [by Rossolinski-Liebe] on the party’s ideological origins… [and] succeeded in forcing all Ukrainian institutions to cancel [his] lectures about the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) and its leader Stepan Bandera.”

The only lecture that far-right nationalists failed to cancel was held at the German embassy. Dozens of people from Svoboda protested the event, including Andrii Illenko, the head of its branch in Kyiv, and now the party’s second in command. An article by Illenko, “Is dialogue possible with Ukrainophobes?” subsequently appeared in “National Tribune,” the US edition of the OUN-B newspaper, published by the Ukrainian American Freedom Foundation.

The “World Conference of Ukrainian Statehood Organizations,” or international coordinating body of OUN-B “facade structures,” met that spring in Munich. The OUN-B conference, perhaps barking more than biting, called for a Ukrainian boycott of German products, and for protests to be held outside German government and diplomatic buildings, in order to punish the Germans for Rossolinski-Liebe’s lecture. Later in 2012, the Banderite “World Conference” tried to defend Svoboda in a letter to the president of the European Parliament: “Of course, there are members of ‘Svoboda’ which are racists, anti-Semites and xenophobic, just as they are in the ranks of the Republican Party in the United States or any other large political party…”

Svoboda entered Ukrainian parliament after capturing an unprecedented 10% of the vote in the October 2012 elections, granting them 37 seats. The party held its annual congress in early December, at which Australian OUN-B leader Stefan Romaniw could be seen sitting in the front row with a big smile on his face. It was this congress at which Oleh Tyahnybok was infamously pictured making a Nazi salute, or so it seemed. Four days later, a massive fight broke out in the first session of Ukraine’s new parliament, with Svoboda politicians apparently leading the charge. Also participating in that brawl was Oleh Medunytsia, who recently succeeded Romaniw as OUN-B leader.

By 2013, the OUN-B’s “Nationalist portal” (UkrNationalism.com) defined the “organized nationalist movement” as the Svoboda party, the OUN-M, the OUN-B and its front groups, as well as the “Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists,” an apparently independent political party that represented OUN-B in the 1990s. Svoboda played an important role in the 2013-14 Euromaidan protest movement that culminated in the “Revolution of Dignity,” or “neo-Nazi coup,” take your pick. Regardless, for most of 2014, Oleksandr Sych served as Vice Prime Minister of Ukraine. “Who exactly is governing Ukraine?” asked The Guardian, which described Sych as “an anti-abortion activist [who] once publicly suggested that women should ‘lead the kind of lifestyle to avoid the risk of rape, including refraining from drinking alcohol and being in controversial company’.”

Yuriy Syrotiuk, the Svoboda chief of political education, allegedly named the “Revolution of Dignity.” He joined Svoboda in 2008, after becoming a leading member of Stepan Bandera’s Trident, a paramilitary organization that parted ways with OUN-B and years later formed Right Sector. In 2012, when Kyiv had its first gay pride parade, Syrotiuk called it “an act of aggression,” and when Ukraine sent a black singer to Eurovision, he reportedly “went public with his contention that her race makes her unfit to represent Ukraine in the European contest.” Meanwhile, Syrotiuk hired a Portuguese Banderite as an advisor—Pavlo Sadokha, apparently the OUN-B point person in Portugal, and a regional vice president of the Ukrainian World Congress. The following year, Syrotiuk traveled to Germany to meet with Ukrainian Nazi death camp guard Ivan Demjanjuk’s lawyer. The OUN-B’s “World Conference of Ukrainian Statehood Organizations” also came to Demjanjuk’s defense.

By the end of 2013, Svoboda seized the Kyiv city council building and made it their “temporary headquarters.” In December, a Svoboda politician formed a coordination center for the Euromaidan to reach Ukrainians abroad. He did so with Mykhailo Ratushny, the OUN-B affiliated president of the Ukrainian World Coordination Council, and his vice president, Stefan Romaniw, the OUN-B leader and secretary general of the Ukrainian World Congress. Ratushny grew close with Svoboda’s “commandant of the revolutionary Kyiv City Council.”

In the coming weeks, Syrotiuk initiated the first “Bandera Readings” in the occupied city hall to coincide with the 85th anniversary of the “Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists” in Vienna that established the OUN. The Bandera Readings became an annual event organized by Syrotiuk and spearheaded by prominent Banderites from the Svoboda party and the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists. Over the years they have been joined by representatives of OUN-M, Right Sector, C14, Azov, and other far-right groups. Presumably the goal is to promote the total Banderization of Ukrainian society, and the unification of far-right nationalists.

Syrotiuk established the “Ukrainian Studies of Strategic Research” in connection with the Bandera Readings. This organization’s board includes Volodymyr Tylishchak, the deputy head of the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory (UINM) since 2014 and a former contributor to “Path of Victory.” Although OUN-B member Volodymyr Viatrovych no longer directs the UINM, far-right nationalists are still embedded in this government institution, like former Svoboda activist Roman Kulyk.

During the summer of 2015, the Svoboda party violently protested a parliamentary vote to amend the Constitution of Ukraine and give autonomy to the eastern separatist regions as part of the Minsk peace process. With few remaining members in parliament, Svoboda clashed with police outside the building. Yuri Syrotiuk was charged with “participating in mass disorder” after someone threw a grenade, which killed several police officers and injured “more than 140 people.” The OUN-B rushed to Syrotiuk’s defense, ostensibly as a political prisoner. Recently he posed with the OUN-B newspaper as a grenade launcher operator in the Ukrainian army.

In 2018, Yuri Syrotiuk participated in an event at the OUN-B headquarters building as a speaker alongside the “Path of Victory” editor and Australian OUN-B leader. They presented a new book of writings by Dmytro Myron-Orlyk, a WWII-era OUN-B leader in Ukraine. Although the Germans killed him in 1942, Myron-Orlyk advocated “purging” Ukraine “of alien racial, Muscovite and Jewish elements.” Among those in attendance was Andriy Tarasenko, the leader of Right Sector, who “finally” met the OUN-B chairman.

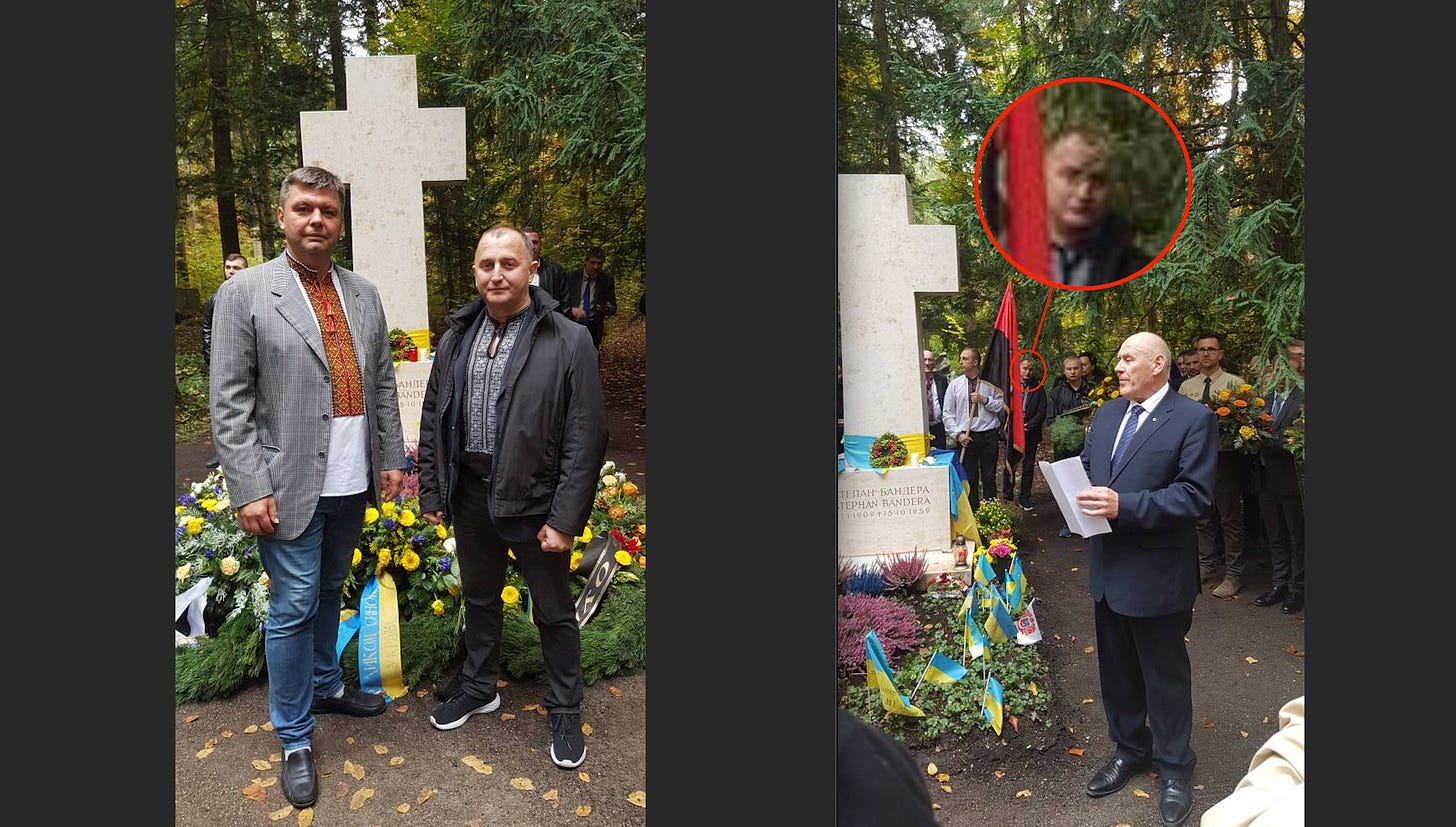

A year later, Syrotiuk wished a happy 90th birthday to the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists. “It’s too early to put an end to the OUN,” he said. Oles Horodetsky, the principal OUN-B representative in Italy, commented, “The goal remains the same, and methods may change depending on the historical moment. The OUN remains the standard of a statist, noble, effective, Ukrainian-centered force! Thank you for posting!” Later that year, Syrotiuk and Horodetsky took a picture together at Stepan Bandera’s grave in Munich amidst an OUN-B pilgrimage for the 60th anniversary of Bandera’s death.

In early 2020, Yuri Syrotiuk joined a special committee formed by the OUN-B to publish a new collection of Stepan Bandera’s writings. Svoboda ideologist Oleksandr Sych wrote the preface to the book, which was published in 2021 with support from Australian Banderites. Syrotiuk’s presentation of the book was a highlight of the 2021 “Bandera Readings.” Other speakers included the chief ideologue of the Azov movement, killed by the Russian army in March 2022, and the young leader of the violently anti-LGBT organization, Tradition and Order. The latter followed a pre-recorded message from Stefan Romaniw and started speaking with the Australian OUN-B leader still frozen on screen behind him.

Last year’s “Bandera Readings,” held a few weeks before Russia invaded Ukraine, had a viral moment when the leader of the (formerly Svoboda-affiliated) neo-Nazi organization “C14,” sitting next to the leader of Right Sector and Yuri Syrotiuk, boasted about the international crisis that began in 2014, “we have started a war that has not been seen for 60 years,” and “Maidan was the victory of the nationalist ideas…”

Nationalists were the key factor there, and clearly at the frontlines. Now there is a lot of speculation, saying “well, there were only a few Nazis” — LGBT, and foreign embassies saying — “there were not many Nazis on Maidan, maybe about 10%…” The thing is… those 10%, maybe even less, 8%… they are much more effective in the proportion of influence… If not for those 8% the effectiveness would have dropped by 90%… If not for nationalists that whole thing would have turned into a gay parade.

Whereas the vast majority of OUN-B members outside Ukraine are descendant of Banderites who emigrated after World War II, the Svoboda party has had more success reaching Soviet-born (“4th wave”) Ukrainian Americans. Diaspora Banderites often snubbed their noses at the newly arrived “Soviet people,” who eventually formed their own nationalist organizations.

Svoboda’s outreach to the Ukrainian American community was in full swing by 2012. That spring, party leader Oleh Tyahnybok marched in Chicago, where he has a cousin—Alexander, a Trump supporter who turned on McCain. The “American cell” of Svoboda is mostly based in the Chicago area, where it is led by Rostyslav Hrynkiv, who apparently works for the Illinois Department of Human Services and once alleged being the victim of anti-Ukrainian discrimination after being fired by the Chicago North Local Census Office. Hrynkiv and friends can take credit for the numerous Svoboda flags often seen at Ukrainian events in Chicago over the past decade. In 2018, they brought Yuri Syrotiuk to Chicago for a “Bandera Readings” event.

Svoboda has also been represented in the US by Natalia Yarova, the head of the Chicago branch of “New Ukrainian Wave,” established in 2007. She attended a Svoboda congress before the 2012 parliamentary elections. The Svoboda party has maintained ties to New Ukrainian Wave, which eventually joined the (Banderite-led) Ukrainian Congress Committee of America as one of its token “4th wave” member organizations. The other is “Orange Wave,” also based in Chicago, which is tied to the “Greywolves Company,” a Ukrainian Insurgent Army re-enactment group that regularly appears at local Ukrainian nationalist events and has repeatedly marched with “Svoboda-US.”

Since 2014, New Ukrainian Wave’s cover photo on Facebook has been a picture from Oleh Tyahnybok’s meeting with their chapter in Philadelphia, after visiting Chicago in the spring of 2012. Since Russia’s invasion, the organization has stepped up support for the Svoboda-linked Carpathian Sich battalion.

Svoboda’s point person in New York is a friend of the “Bandera Lobby.” As of 2019, Andriy Dzoban was the deputy head of the Ukrainian Congress Committee of America chapter in Riverhead, New York. That year, he signed a far-right petition that was presented to the Mykolaiv city council in southern Ukraine, calling for a 93 year old veteran of the Waffen-SS to be awarded the title of “Honorary Citizen of Mykolaiv.” In 2017, Dzoban spent several days at the OUN-B affiliated summer camp in Ellenville, New York. That summer, he took a couple photos there with “Path of Victory” editor Viktor Roh, and later that year appears to have accompanied him to Ellenville from Long Island for the US Banderites’ annual ideological winter camp.

What were they doing on Long Island? Dzoban and Roh presented a sort of Nationalist lifetime achievement award to a 93 year old Banderite on behalf of the OUN-B and the Ivano-Frankivsk Regional Council (Oleksandr Sych). Anna Karvanska-Baylyak, a longterm OUN-B member, was married to a Ukrainian veteran of the Waffen-SS, and donated many of his belongings to the Banderite “Ivano-Frankivsk regional museum of liberation struggle.” After World War II, she got married, and was sentenced to 14 years in prison in Poland. Her husband joined the U.S. army and deployed to Korea with an engineering battalion. They reunited in the United States after the Red Scare. Thanks to the GI Bill, he got an engineering degree, and “embarked on a successful career as a civil engineer, retiring from his position with New York City Housing Authority in 1991.”

When Andriy Illenko, the deputy head of the Svoboda party who protested Grzegorz Rossolinski-Liebe’s 2012 lecture in Kyiv, visited New York City in 2016, he met up with Andriy Dzoban in “Little Ukraine,” Manhattan, and visited the headquarters of the Ukrainian Congress Committee of America. “New Ukrainian Wave” co-sponsored the meeting with the Organization for Defense of Four Freedoms of Ukraine, an OUN-B “facade structure.” Last October, Yuri Syrotiuk gave thanks to Dzoban, Roh, and Ukrainian American OUN-B attorney Askold Lozynskyj for sending night vision goggles to his platoon. Lozynskyj, of course, is an architect of the drama in “Little Ukraine” that gave rise to this blog.

Obviously, Svoboda’s foreign contacts are not limited to the United States. In 2015, the party’s chief of international relations was appointed to the Ukrainian Ministry of Information Policy as an advisor on communications with the Ukrainian diaspora. By that point, Taras Osaulenko had visited Svoboda supporters in Germany and met with Ivan Demjanjuk’s lawyer, participated in a neo-Nazi conference in Sweden, networked with Italian neo-fascists, and served as the head of Oleh Tyahnybok’s campaign office. Rather than try to complete an international overview of Svoboda’s reach, let’s look at three “random” countries: Germany, Italy, and Spain.

Oleksiy Yemelianenko, born in Soviet Kiev, moved to Frankfurt, Germany in 2000 at the age of 25. Ten years later, he became the Svoboda party’s representative in Germany, and a proxy for Oleh Tyahnybok. Yemelianenko appears to have returned to Ukraine in 2015 to run for Kyiv City Council as a Svoboda candidate. In the meantime, he led the Ukrainian community in Frankfurt and served as deputy chairman of the Central Union of Ukrainians in Germany, a member of the Ukrainian World Congress that developed ties to the Svoboda party. In 2013, reportedly “unafraid of the historic parallels,” Svoboda created a party branch in Munich, and three years later, Tyahnybok visited supporters in Germany accompanied by a photography exhibit about the Carpathian Sich battalion, or “Svoboda legion.”

Natalia Tsebryk appears to be Svoboda’s point person in Rome, and at least used to be a board member of the General Union of Labor (UGL), which Politico described as “a far-right-affiliated Italian union” after it signed a deal with a coalition of food-delivery companies (including Uber) in 2020. According to Alba Sidera Gallart, a journalist focused on the Italian far-right, “For some time now, Italy has had trade unions that are openly linked to right-wing parties, like the UGL: indeed, the latter’s conference was attended not only by [Matteo] Salvini, but also by representatives of the right wing of Silvio Berlusconi’s party, the post-fascist Brothers of Italy party led by Giorgia Meloni, and even Simone di Stefano, the leader of the neo-fascist group CasaPound.”

During the summer of 2015, after a shootout between police and members of Right Sector in southwestern Ukraine, Tsebryk joined a flash mob organized by Italian Banderites in front of the Colosseum to express solidarity with the notorious far-right movement. Two years later, for the fake 75th anniversary of the OUN-B’s Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), Tsebryk welcomed Andriy Illenko, the deputy leader of the Svoboda party, to Rome for a “historical (Banderite) reading” event with Yuriy Tykhovlis, an assistant to the secretary of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace. Tykhovlis, like Tsebryk, hails from Ternopil. The Ukrainian nationalist Vatican official is now a senior regional coordinator for Eastern Europe at the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development.

The neo-Nazi leader of Svoboda in Spain is Ivan Vovk, who founded the Ukrainian Patriotic Association (UPA) Volya (“Liberty”), an organization for Spanish Svoboda supporters. That was in 2013. The following year, they created a newspaper, “Idea of the Nation,” referencing the neo-Nazi wolfsangel symbol associated with the “social nationalists” from the SNPU, Svoboda, and Azov. In 2015, Svoboda’s not-so-crypto-Nazi youth organization (Sokil, “Falcon”) established a Spanish branch, and Vovk attended their inaugural meeting in Madrid. Vovk is standing in the middle below, wearing a Sokil shirt.

I don’t know enough to tell you about the relationship between the Svoboda and OUN-B supporters in Germany, Italy, and Spain. There may be some overlap, and also some tension. Take for example the new OUN-B leader, Oleh Medunytsia, who served in Ukrainian parliament with the oligarchic “Fatherland” and “People’s Front” parties. “It’s disgusting,” the controversial Svoboda politician Iryna Farion said of Medunytsia’ rise to power in the Bandera Organization.

In 2014, after the Maidan coup, Farion was passed over as the Minister of Education in favor of Serhiy Kvit, a prominent OUN-B member. “Ukrainian Academic Freedom and Democracy Under Siege,” historians Per Anders Rudling and Jared McBride warned in 2012, after the Rossolinski-Liebe affair, and Kvit expelled the “left-leaning” Visual Research Cultural Center from the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. “Dr. Kvit,” they noted, “is known in Ukraine as the author of an admiring biographer of the Ukrainian fascist thinker Dmytro Dontsov and as a Svoboda supporter.”